Phase shifts are a hidden part of many equalizers that can often destroy your mix. It pays off to know why does EQ change phase and whether you can prevent it.

What is phase shift in equalization?

Phase shift is a side effect of equalization you can imagine as an incredibly small delay applied to frequencies affected by an equalizer. This (usually unintended) delay changes the way frequencies in a sound relate to each other.

Since in music many sounds and instruments overlap and play together, this means that phase shifts applied to a single sound can change the perception of the whole mix under certain conditions.

If you had a situation, where specific (usually extreme) equalizer settings made the sound way different from what you expected, you have most likely heard phase shift affecting it.

After reading this, you may think that phase shifts are inherently bad and you should avoid them at any cost, anytime. The truth is that in most situations, they will not cause much trouble in the mix, especially if you use the equalizer in a proper way.

There are also situations (although rare) where phase shifts caused by an equalizer are helpful and improve the mix.

Why does EQ change phase?

Changes in the frequency spectrum (that are expected from equalization) and changes in the phase response (that are caused by phase shifts) usually happen together. Trying to answer the question of whether it's the equalization that causes the phase shift or whether it's the phase shift that makes the frequency spectrum change is difficult and has little sense from the practical point of view.

To help you understand this, we need to take a look at how analog equalizers work. I'm going to keep the explanation as simple as possible.

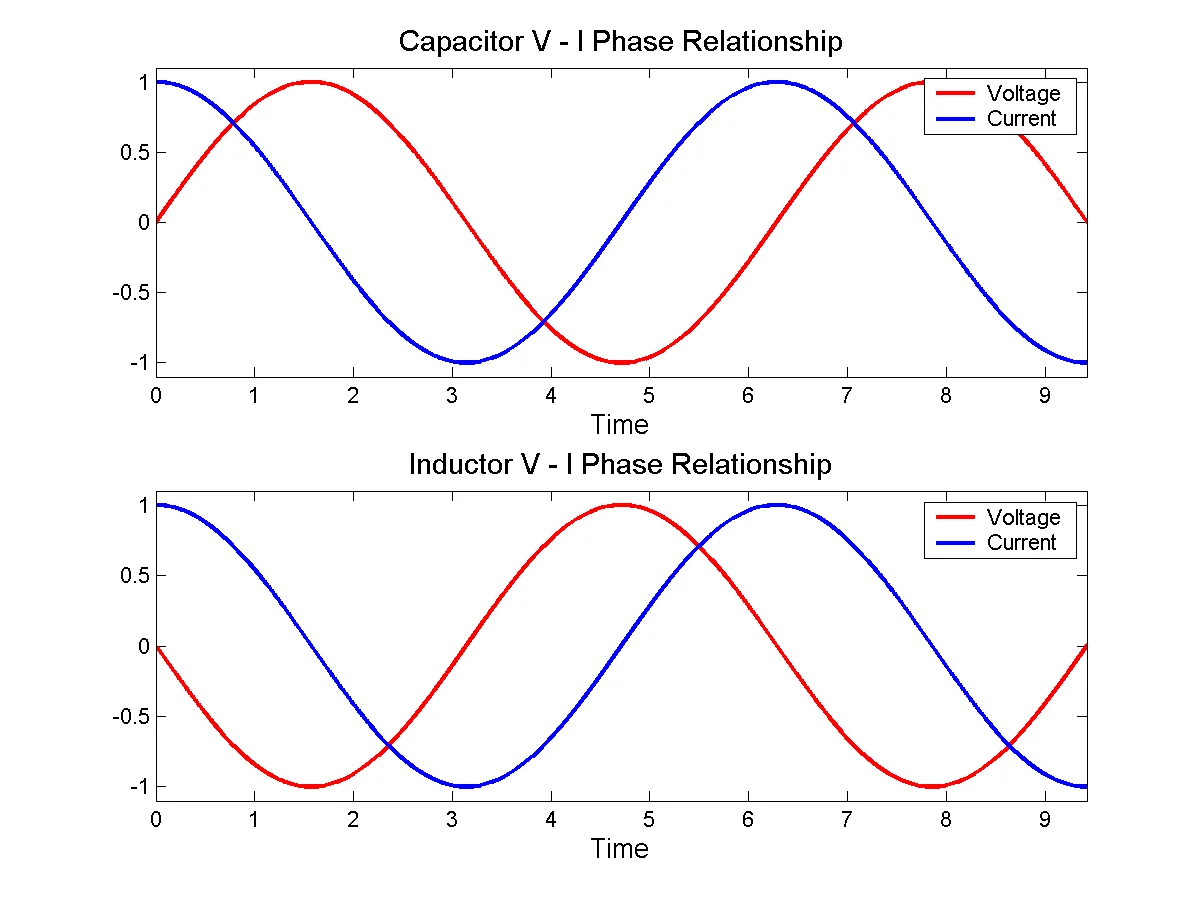

Analog equalizers are made from electric compontents and always have in their design either capacitors or inductors. These elements are known for introducing a phase shift between the voltage and the current. On the picture below, you can see what does it look like in the simplest form:

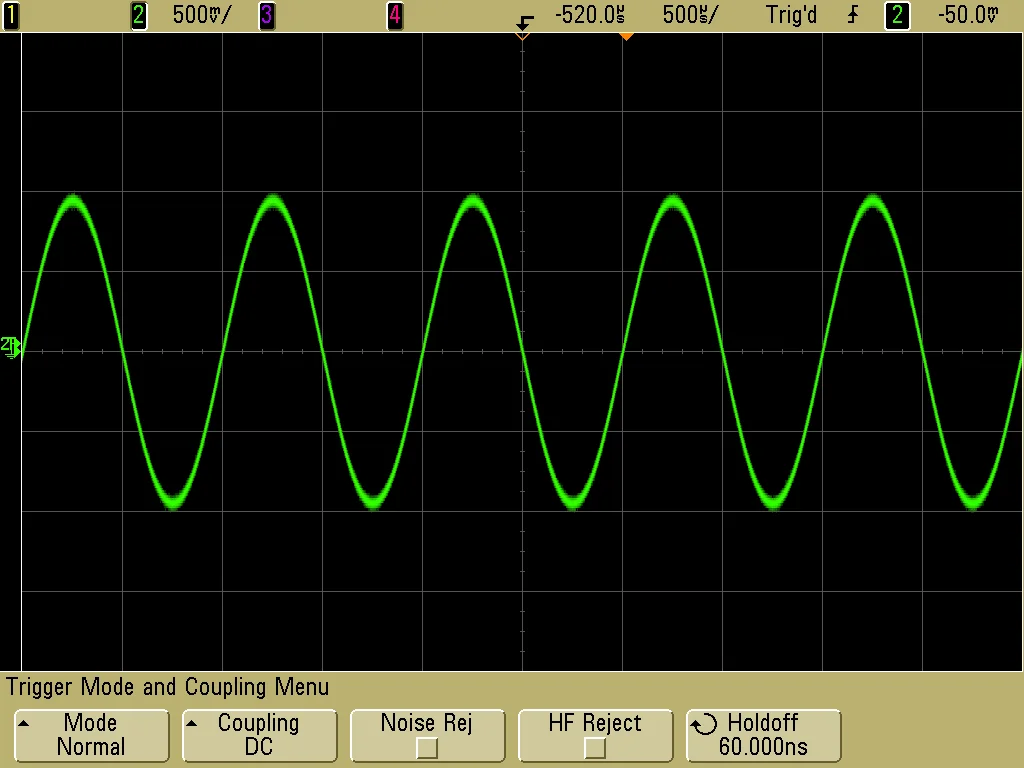

In electronics, sounds are defined as voltage with various amplitude that changes over time. We can observe that voltage using for example an oscilloscope.

For example, this is what does a sine wave look like under the oscillopscope:

Because such sine wave is essentialy a voltage, we can now understand how an analog equalizer with capacitors and inductors inside could cause phase shift and alter the signal. Would that phase shift be identical for all sine waves, regardless of frequency or amplitude?

It turns out that electronic circuits that involve these capacitors and inductors apply different phase shift to signals with different frequency. That signal frequency and added phase shift relationship can be influenced by the electrical circuit design.

Because sounds we usually use an equalizer on are signals with numerous frequencies of various amplitudes, our analog equalizer (where the electrical design doesn't change) will treat each frequency with different phase shift.

Digital equalizers that you use in a form of VST, AU or AAX formats mimic that behavior. Instead of voltage, audio signals are represented by series of 0 and 1 digits. Instead of capacitors and inductors, samples and buffers are used.

How does EQ change phase?

You already know that equalizers, depending on their design apply different phase shift. This also applies to the way we set up the equalizer, and it doesn't matter whether you use an analog or digital one. It only seems logical that (for example) we won't apply any phase shift if the equalizer is bypassed.

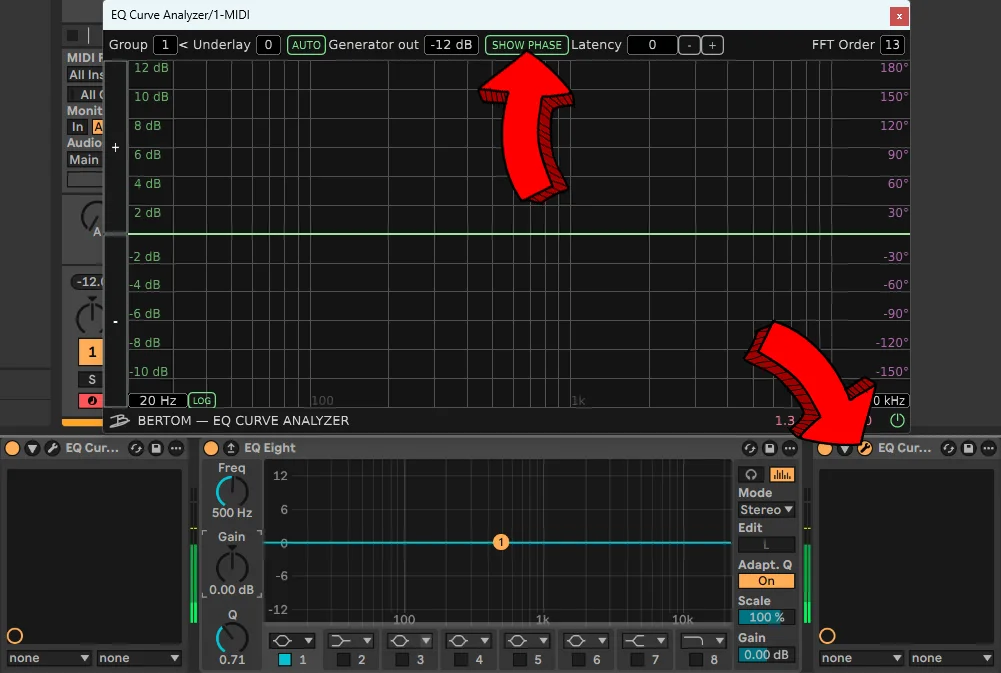

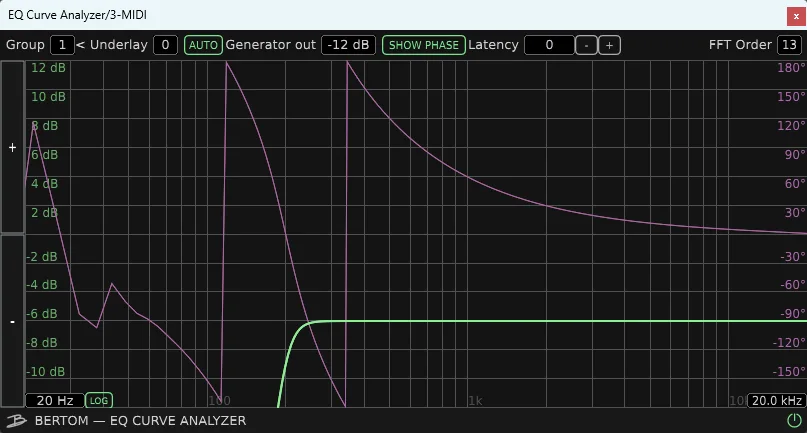

It is possible to observe the phase shift an equalizer introduces using a specialized software. One example would be the DDMF Plugindoctor, but another recommended solution I will use today is the Bertom Audio EQ Curve Analyzer.

To see both frequency and phase response of any equalizer, simply put it in between two instances of the EQ Curve Analyzer plugin:

Then, open the EQ Curve Analyzer to the right and click the "Show Phase" button:

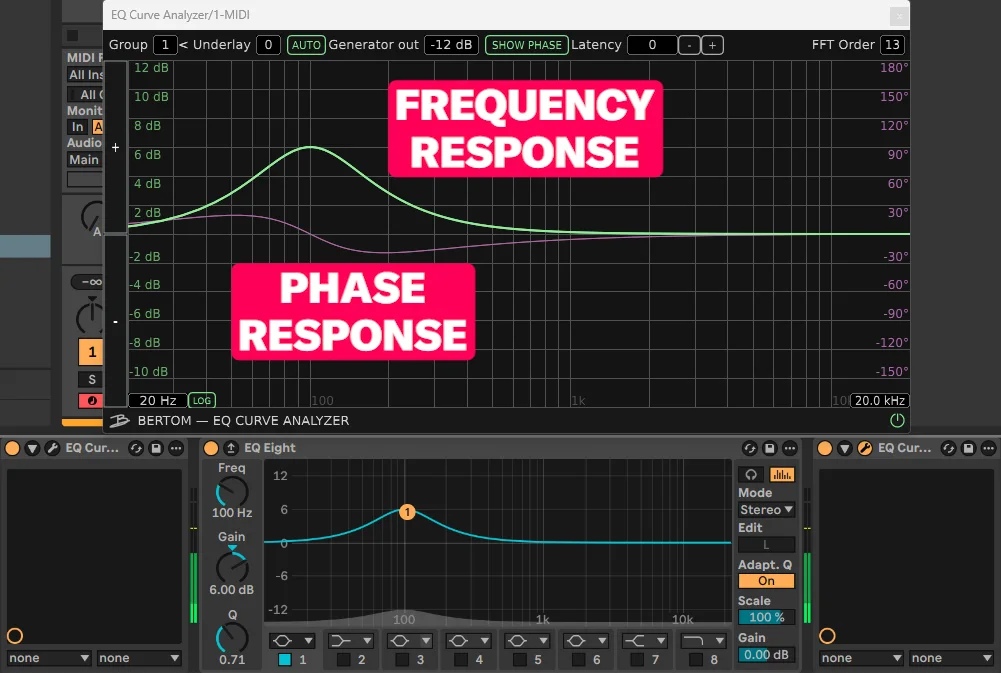

Now we can tweak the equalizer in the middle to see both frequency and phase response. At this moment, the equalizer doesn't apply any boost or cut, and as we can see in the screenshot, the EQ Curve Analyze plugin doesn't show any phase shift.

Let's change that and apply a 100Hz boost using a peaking filter:

While the amount of attenuation is shown in decibels, phase shift is expressed in degrees. The reason for using degrees as a measurement unit for phase shift is explainable with some mathematics, but we don't need that knowledge to know how to use an equalizer to be in better control of sound.

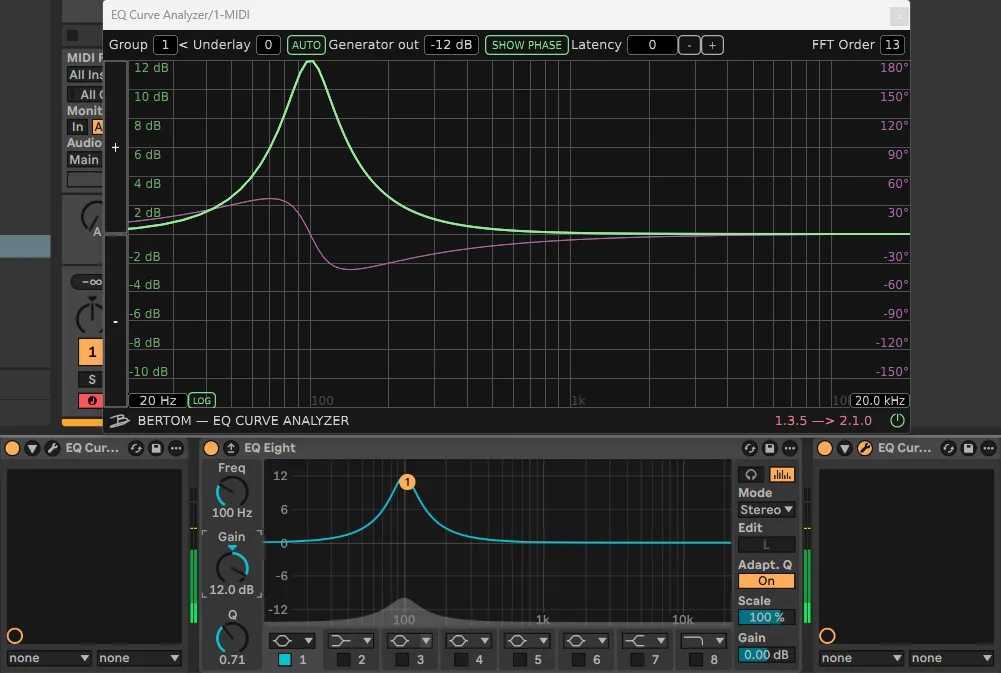

Phase shifts are applied not only to the cutoff frequency of an equalizer filter, but also to the frequencies around it. The distribution and amount of phase shift added by an equalizer will vary with both amount of boost or cut applied:

or the filter bandwith you control with the Q control:

Peaking filters in the equalizer, even with large Q values give little phase shift and are perfectly safe to use.

Let's see the phase shift of another filter type - a shelf filter:

Shelf filters are also gentle when it comes to the phase shift added. A general rule of phase shift is following:

The more gentle and less aggressive the equalizer curve is, the less phase shift is added.

Let's see an example of a filter that is much less softer than either peaking or shelf filter. I'm talking about the notch filter that has infinte attenuation at the cutoff frequency:

Not only the amount of phase shift is larger, but its distribution looks odd, increasing the chance of affecting the sound negatively.

But notch filters are used very rarely (personally, I don't use them at all when mixing), so we don't need to worry much about phase shift caused by them.

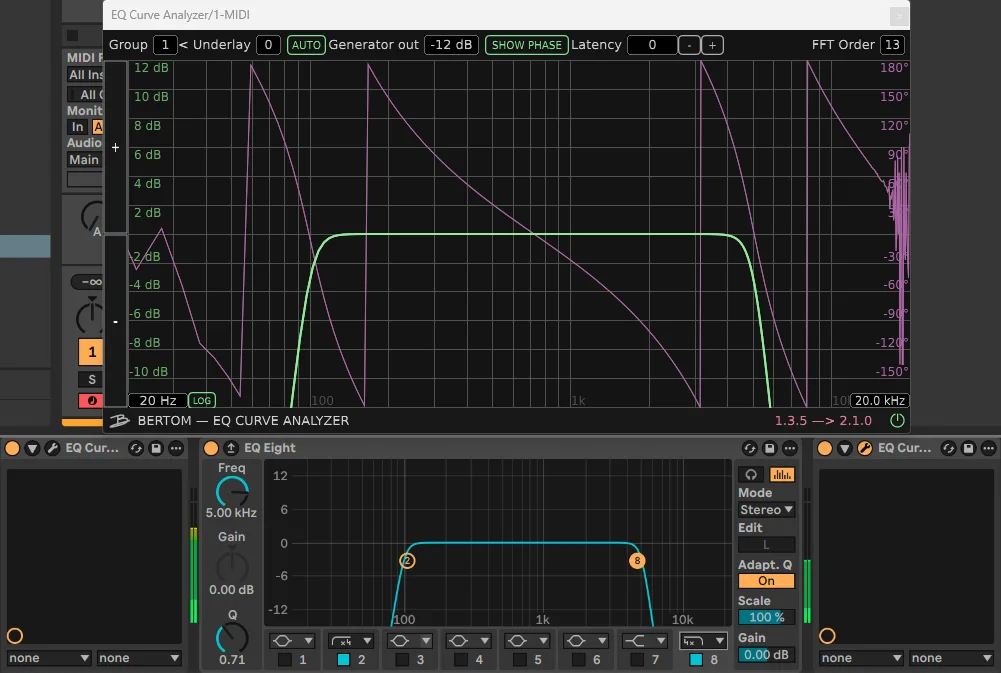

The type of filters that truly shows the pontential danger of phase shifting is both low and high-pass filter:

Both filters remove much more frequency content than for example a set of both low and high shelf filters - more phase shift added should not be surprising.

Now let's take things to the extreme. I will increase the slope of both filters (that, by the way create together a bandpass filter):

Now that's a large amount of phase shift!

Can you hear phase shifting in a mix?

While on the picture phase shifts look significant, very often their effect on the mix is inaudible.

However, there are two situations you can stumble upon when mixing a track that will make phase shifting create an audible difference in sound. Fortunately, they are more of a mistake on your end you can easily prevent once you are aware of how you use the equalizer.

Using brickwall filters

The first situation will relate to using mostly high-pass filters. As you have seen in screenshots above, both low and high-pass filter can add a lot of phase shift. At the same time, low and high-pass filters are very useful in mixing and you will be using them regularly.

The most common use case of these filters in mixing is removing useless low-end from certain sounds with a high-pass filter. Take for example a snare drum I want to mix with the bassline:

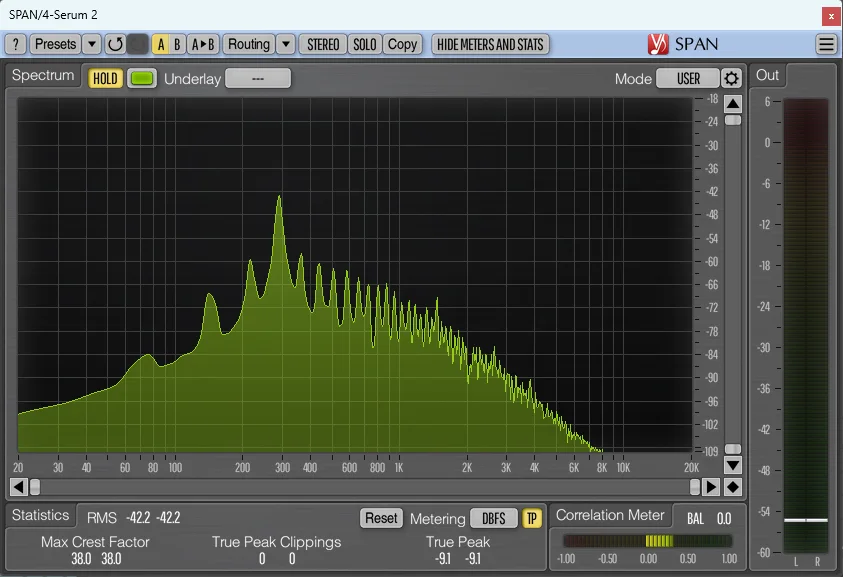

The snare packs a lot of punch, as well as some pretty heavy low-end. A quick look at the frequency spectrum shows how many low frequencies below 200Hz this sample has:

Of course, if I try to simply play such snare alongside the bassline, low frequencies from the bass sound will overlap with the low-end of the snare. Even if the bass was sidechained, low frequencies in this snare sound bad and make the sound too heavy and bloated.

That's why a high-pass filter that removes the muddy sound is necessary. A mistake a beginner producer could make is to think that the more precisely a high-pass filter removes the low-end, the better the mix will be.

With modern equalizers like FabFilter Pro-Q 4, aggressive and precise filter shapes are within reach of a few clicks. For example, a low-pass filter in FabFilter's equalizer can have 10 different shapes (or slope values to be precise). In the examples below, I will be using a slightly older version of the Pro-Q equalizer, but the filter types are identical:

This article has affiliate links. By using them to buy plugins, you help both plugin companies and me. If you like what you read, any support is appreciated.

Filter's slope controls how quickly frequencies below the cutoff frequency are removed from the sound. The most aggressive setting is the Brickwall filter that guarantees most precise cuts (and in theory, best results):

You can see I put this brickwall filter right at the 200Hz peak, where the punch from the snare sits. In that way, all heavy low-end that would conflict with low frequencies of the bassline is removed.

However, after using an equalizer that way, the snare drum sounds unnatural. It's as if the snare got extra "tail", making it more similar to a tom sample:

This sound is a result of massive amounts of phase shifts that influence the snare sample. This phenomenon is called "post-ringing", where phase shifts add a ringing effect to the sound.

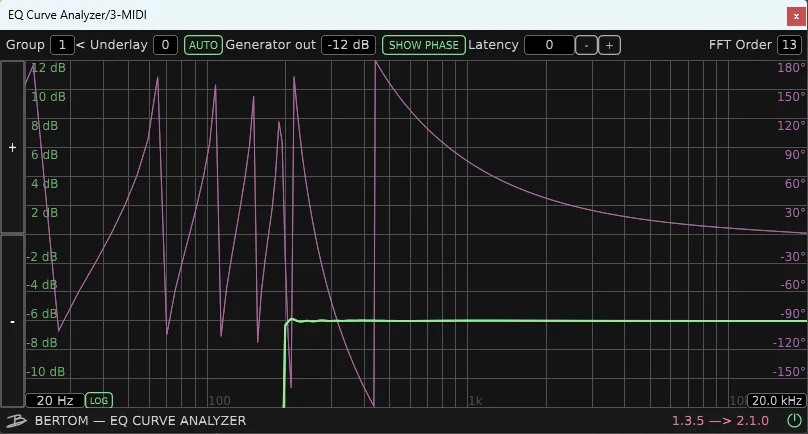

You might be interested now in seeing how much of a phase shift this brickwall filter adds. Here's what does the EQ Curve Analyzer look like when I use it on FabFilter's equalizer:

Phase shifts mess around with our 200Hz peak a lot - no wonder we can hear their effect on the snare drum's attack.

This post-ringing effect can be easily avoided if you use a less aggressive filter shape. In the Pro-Q equalizer, I will use now a 48dB/oct high-pass filter that has a more gentle shape:

Despite less "precise" shape than a brickwall filter, this high-pass filter is still very effective in removing the snare's low-end - this time, without causing any post-ringing:

The phase response of our 48dB/oct filter looks much cleaner. There are less phase shifts that could impact the sound negatively:

We can wrap this example with a simple conclusion: avoid extremely aggressive low and high-pass filter shapes.

Personally, when I'm mixing tracks or giving private techno production lessons, I always show that you can successfuly filter out unwanted frequencies with filters whose slope setting ranges from 6dB/oct to 48dB/oct.

There are even situations where a less aggressive filter beats the sharp one with high slope. This happens often when applying low-pass filters - those that remove unwanted high frequencies more gradually tend to sound more natural and pleasant.

Equalizing a group of similar sounds

The second example relates to equalizing a group of sounds. For the phase shift to create an impact, two conditions must be met:

- Sounds must play together at the same time.

- Sounds must sound similar.

Such situation happens more often than you may initially think. What makes this scenario more important and realistic is that it mostly happens to the most important sounds in the mix. Here are a few examples:

- Vocal tracks - a singer records multiple takes of the same lyrics, with slightly different tone or accent. Later, these takes are played together to create a more dense, full vocal.

- Acoustic drum recording - to capture all the sounds coming from the percussion kit as reliably as possible, multiple microphones can record the same instrument from different positions and angles. Not only all recordings will be synchronized - they will also share similarities in sound.

- Synthesizer layering - sometimes to create a powerful lead sound in electronic music, multilple synthesizer instruments are playing together. Each synthesizer provides a sound with a different set of tones, but all of them can play the sound with identical pitch and rhythm.

Whenever you come across such scenario in your mix, you should think not only about how you will equalize the sound, but also about where the equalizer should be.

To show you how does it work, I have created a simple pluck in Serum 2 synthesizer that uses 2 oscillators:

And here's what does the synthesizer sound like:

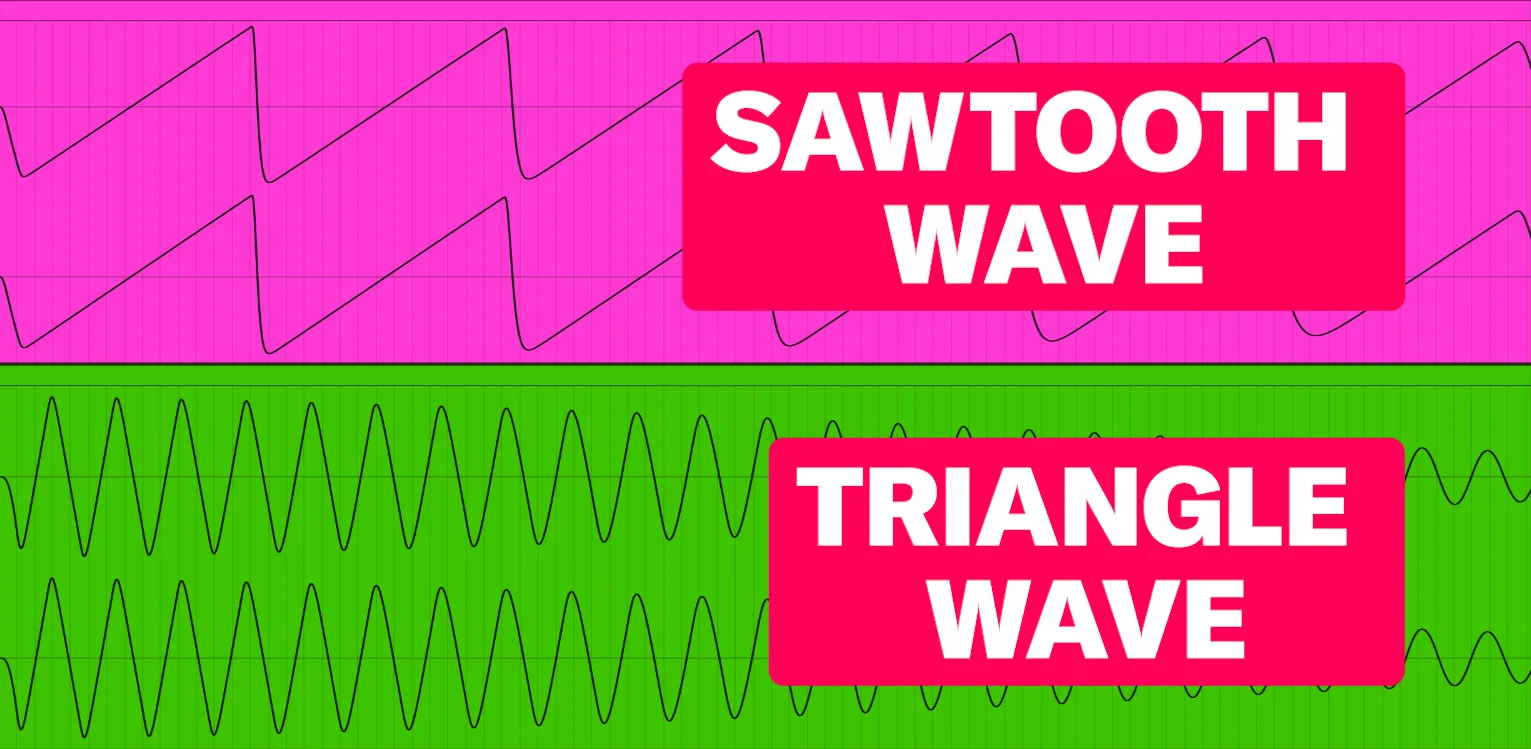

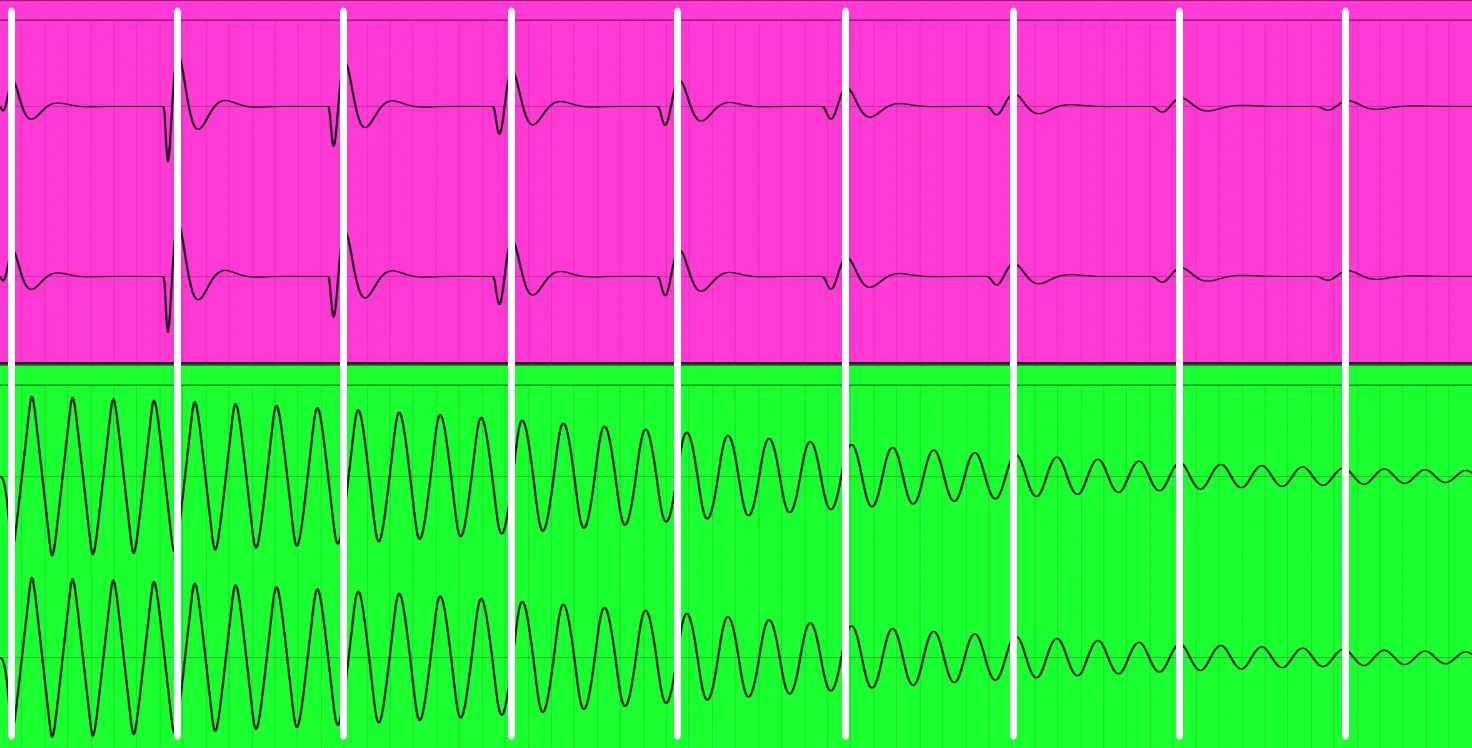

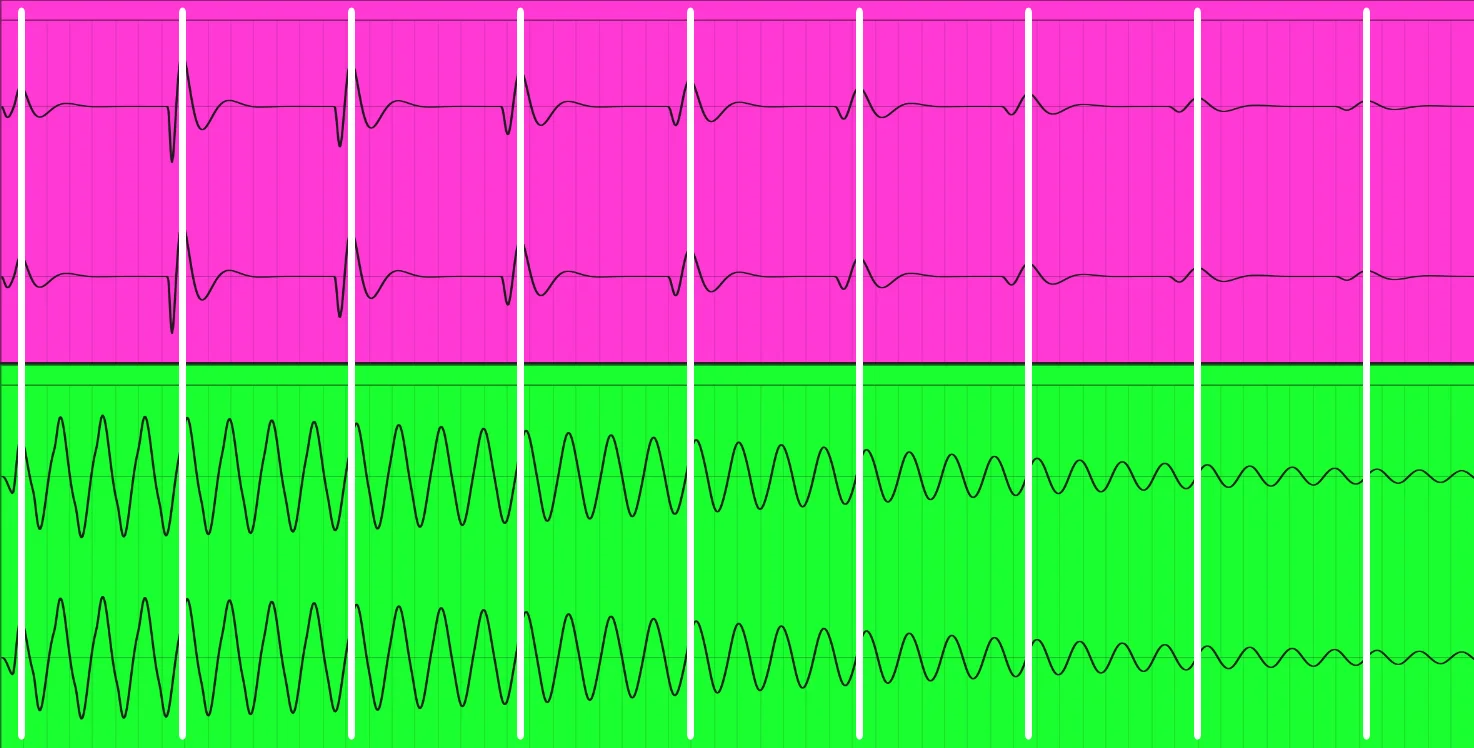

I have set up the oscillators in a way that both the sawtooth and triangle waves are synchronized. Here's what these waveforms look like if I export them to separate audio tracks:

Notice that even though the triangle wave is pitched up by 2 octaves in relation to the sawtooth one, both waves are synchronized - positive and negative peaks align and both waves begin playing with the same initial phase (position):

Let's listen to these waves in solo. At first, here's the sawtooth wave:

And now, I'll play you the triangle wave:

Our oscillators are playing together at the same time and they sound pretty similar. Now let's talk about equalization.

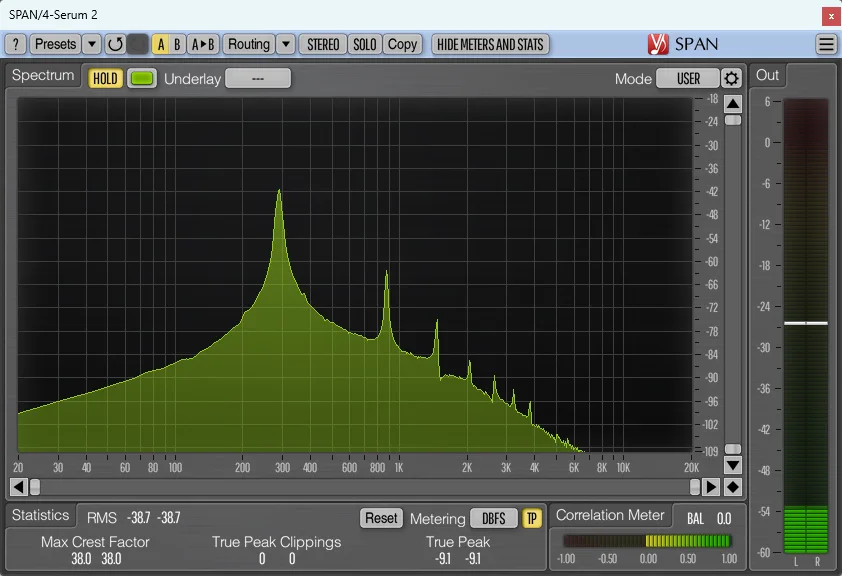

Just like with the snare drum from the previous example, this synthesizer also has low frequencies:

If I wanted to play this synth along with some bass, I would (again) overlap the low-end from the synth with the low-end of the bassline. Once again, we have to use a high-pass filter to remove low frequencies from the synth.

But here's the catch: the low-end in the synthesizer comes only from the sawtooth wave:

While the triangle wave has its peak at 297Hz:

Though you can also see some frequency content below that peak in the triangle wave, it's roughly 46dB quieter than the 297Hz peak. We can safely ingore that and say that our triangle wave has no low-end.

To remove the low-end from the synthesizer, an equalizer can be used in two different places. It sounds reasonable to remove from the sound as little frequencies as possible, which means that we should use a high-pass filter only on the sawtooth wave:

If we do that, the low-end from the whole synth disappears:

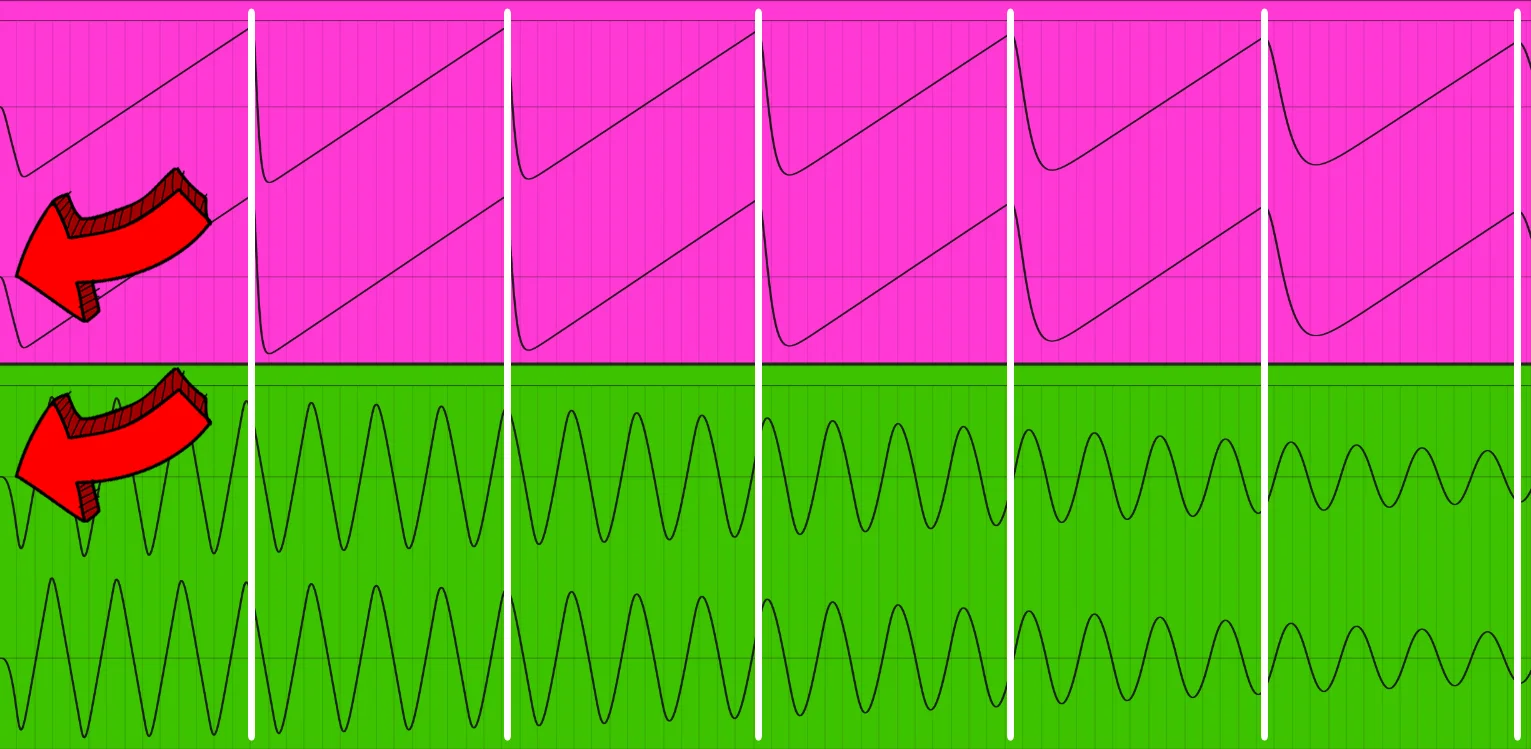

But something interesting happens to the sawtooth wave. Because of a high-pass filter used, a phase shift is added.

Because a high-pass filter affects the sawtooth wave only, that wave is going to be not synchronized with the triangle wave anymore:

This will make the synthesizer slightly less clicky and clean in the beginning:

Let's see how the synth will look and sound like if an identical high-pass filter is used on both oscillators at the same time:

The high-pass filter I had in the OSC tab is now turned off. As a result, when I export both sawtooth and triangle wave again, those waves are synchronized much better than previously:

The resulting synth, despite the same high-pass filter used will sound now cleaner - especially in the beginning:

Although the difference in sound seems so little it doesn't make any sense to pay attention to where you use an equalizer, in the context of equalizing layered percussion sounds (where transients play a big role in your mix), this knowledge may come handy.

My conclusion for this example is following:

Try to equalize as much as possible a group of samples that play together before making adjustments to individual sounds within that group.

In that way, you will reduce the amount of phase shifting added that may change the relative position of sounds.

How to prevent phase shifting in the mix?

As you've heard in previous examples, careless equalization may bring to the sound more phase shifts than necessary. And in many cases, these phase shifts are going to make your mix sound worse and less precise.

That is why it's good to remember a few rules that will keep your percussion, vocals and other important sounds in your track in best shape:

- Avoid using aggressive low and high-pass filters, as well as the notch filter. From my experience, I can count on a single hand the number of times I needed a notch filter. For low and high-pass filters, I avoid using filters with a slope higher than 48dB/oct.

-

Equalize a group of sounds whenever possible. This will keep the sounds' relative position more than relying on equalizing individual channels. I usually begin equalizing the group of sounds before diving into individual channels.

This does not only keep individual channels "synchronized", but it also makes me use less equalization in total. That's because more often than not, all the sounds within the group benefit equally from the equalization I would have to apply to individual channels otherwise.

Double-check the volume levels. You would be surpised, how often just changing the volume of an instruments seems to fix a problem you thought requires an equalizer.

An example of that can be a situation where hi-hats in your track aren't as upfront as you want.

You can either try to use a high shelf filter to boost high frequencies of hi-hats or turn up the whole hi-hats channel. This will also make the high frequencies of hi-hats louder, as well as the mid ones (which may give a better result than just using a high shelf filter).

You may notice I didn't mention in this article linear phase equalizers that prevent any phase shift, regardless of how aggresively you equalize the sound. That's because these equalizers, while preventing phase shifting (and potentially post-ringing) can introduce another artifact, called "pre-ringing". Pre-ringing hurts most percussive samples and their transients.

There are also a few other downsides of linear phase equalizers that make such effects less useful than is sounds like. But because this subject is wide and broad, I am going to cover it in a separate article that will come soon.